Decrease in Shared Reality Formation in Adolescents Due to Texting

- Sanika Misra

- Apr 2, 2024

- 18 min read

Sanika Misra, Obra D. Tompkins High School

Abstract

Texting has become the predominant method of communication for adolescents. Increased use of texting among this age group can have negative effects on social and relationship development ultimately hindering shared reality formation. Shared reality formation is a psychological phenomena described as the idea that a person has similar inner feelings, beliefs, and world concerns to other people. The impact of texting on shared reality formation has not been researched in adolescents to date. Therefore it becomes relevant to address the following question: How does texting impact adolescents’ ability to form shared realities about the world with others? 14 participants were chosen from the Katy area and they completed various assessments as part of the experiment to provide insight towards the study. The preliminary assessment had participants express their view on whether live action or animated movies are superior. After the 30 minute discussion, participants completed the postliminary assessment which had both open-ended questions and Likert scale statements about how the chosen communication method affected the ability to interpret their partner’s perspective. Likert scale statements revealed that only 25% of texting group participants felt they had a connection with their partner. The lack of connection in the remaining participants expressed misinterpretations of the message’s actual meaning. Therefore, these results indicate that texting does present a significant impact on shared reality formation in adolescents.

Introduction

Communication has undergone substantial change throughout history, from the use of symbols and images to convey information in 500,000 B.C.E. to the improvement of communication in the 19th century, allowing messages to be transmitted over great distances (Novak, 2019). In contemporary society, technology has been utilized as a medium of communication, particularly through texting, which allows for messages to be transmitted instantly. Focusing specifically on adolescents, an age group between 10 and 19, texting has surpassed phone calls and in-person interaction as the predominant method of communication (Graham, 2013). The convenience offered by texting has led to its widespread popularity among teenagers, providing them with the freedom to connect with their peers and “maintain friendships” (Graham, 2013, p. 2). Through texting adolescents enjoy greater communication flexibility due to the ability to “edit messages” and can remain in constant contact “with their parents or guardians” (Graham, 2013, p. 2). However, while online communication can have benefits, Lieberman and Schroeder contend that if it displaces in-person communication it can disrupt social connection by harming well-being and reducing sociality (Lieberman & Schroeder, 2020). Exploring the effects of texting’s increased use among teenagers has become imperative due to its increasing prevalence as a method of communication. Specifically, a crucial concern is to investigate the impact of texting on the social development and formation of relationships in adolescents, with a particular emphasis on its influence on the creation of a shared reality.

Shared Reality Formation

A shared reality is defined as the idea that a person has similar inner feelings, beliefs, and world concerns to other people (Schmalbach et al., 2019). This shared reality instills a feeling of global comprehension as well as social connection. Typically, humans are motivated to create shared realities with others because it forms the groundwork of relationship building and is reported as a key stage of child development (Schmalbach et al., 2019). The formation of a shared reality through in-person communication occurs as an individual interprets the beliefs of others by understanding their nonverbal cues, body language, and natural inflections and cadences. However, according to Echterhoff, this process is hindered in online communication due to the absence of analyzing these signals, thereby affecting the development of a shared reality (Echterhoff, 2013).

Development of Social Skills in Adolescents

Adolescence is a crucial stage for social development in an individual’s life since it allows young people to establish a greater capacity to form stronger relationships with others, which prepares them to take on more complex social roles (Choudhury et al., 2006). As a result, the formation of a shared reality is crucial because at this stage of life, teenagers are aware of when others share their opinions, and knowledge of shared beliefs affects how they perceive others in social situations. Consequently, it is crucial for adolescent groups to have the necessary social skills that allow them to communicate in a face-to-face setting during interviews, class discussions, workplace environments, and other forms of basic communication interactions (Graham, 2013). Although the nature of communication in the world is evolving, these social skills are important for teenagers in different aspects of their lives. Face-to-face contact encourages adolescents to learn from their setbacks and accomplishments while refining crucial social skills. Contrastingly, individuals have a difficult time comprehending one another while communicating through text, which impairs the creation of a shared reality and, as a result, can have real-world repercussions. Additionally, texting encourages “dysfunctional behavior”—texting habits that significantly affect one’s psychological well-being or everyday functioning—and provides adolescents with the “social freedom” to distort their identities due to the diminished influence of social norms (Brignall et al., 2005, pp. 11-12). Increased texting can potentially result in a narrower worldview for individuals and pose communication challenges when interacting with those holding contrasting opinions or perspectives. As a result, these people tend to isolate themselves from individuals and ideas that make them feel uncomfortable, which is unrealistic in a face-to-face setting (Brignall et al., 2005).

Gap Analysis

While there have been studies that highlight the effects of in-person versus online communication on an individual's ability to comprehend others and build relationships, there is a gap in research pertaining to the impact of texting on shared reality formation in adolescents. Specifically, little is known about how communication through texting compromises certain social skills, as teenagers may struggle to effectively understand the opinions of others and establish a shared reality.

Heiphetz, investigates the importance of shared reality formation amongst children for establishing social preferences based on other people’s moral convictions and behaviors (Heiphetz, 2018). Additionally, her research reveals that shared reality formation instills prosocial behavior in children and influences social judgment across development (Heiphetz, 2018). While Heiphetz (2018) focuses on shared reality formation in a face-to-face setting and examines primarily children, there is a gap on how the inability to form a shared reality can affect relationship formation in adolescents, a crucial stage in an individual’s developmental process, and impede the development of necessary social skills. Understanding how texting impacts shared reality development in adolescents can help them become conscious of the possible drawbacks of digital communication and devise solutions to these disadvantages, such as having more face-to-face interactions to create stronger shared realities. Ultimately, given the lack of research on how shared reality formation is impacted by texting in teenagers, it becomes increasingly urgent to address the following question: How does texting impact adolescents’ ability to form shared realities about the world with others?

Methods

Design

This study involved a mixed-methods approach in which participants completed preliminary and postliminary assessments and also took part in an experiment to measure the overall effect of texting on influencing shared reality formation. The experimental design aimed to prove a cause-and-effect relationship between the form of communication and shared reality formation, which could not be established with any other method. For the purposes of the experimental design, there was a control group in which participants interacted face-to-face and an experimental group in which participants engaged through texting. Supplementary Figure 3 presents an open-ended survey conducted prior to the start of the experiment, in which individuals were asked to express their views on whether live action or animated movies are superior. This topic was chosen because it is necessary for people to exchange knowledge about a certain concept that they could clearly discuss for a considerable amount of time in order to create a shared reality. Afterward, participants were randomly paired with individuals in the same group, and they communicated about the same topic for approximately 30 minutes throughout the duration of the experiment. As highlighted in Supplementary Figure 2, the post-experimental questionnaire included open-ended questions about the quality of the discussions, how the chosen communication method affected the conversation, and the extent to which participants understood their partner’s perspective on the subject. To address the subjective nature of the open-ended survey results, I employed the Likert scale, as shown in Appendix A, ranging from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating strong agreement and 5 indicating strong disagreement, which provided me with numerical data that could be compared with other groups using statistical measures such as mean, median, and mode. These statements were used to evaluate various aspects related to the participants’ shared understanding with their partners on the topic. In addition, I observed the behaviors of the participants in the face-to-face group, which further aided in the data collection process and facilitated more accurate conclusions. The information gathered from the test results was then examined to shed light on whether participants were successfully able to communicate thoughts and ideas to establish a mutual comprehension of a particular subject matter. The findings of this study were analyzed utilizing Microsoft Excel spreadsheets and were separated for the experimental group and the control group. 14 participants took part in the experiment, and the findings included responses to Likert scale statements and short answer responses.

Variables

In my research, the independent variable was the differing forms of communication, which are texting and face-to-face communication. This is because researching texting in isolation does not provide insight into how shared reality formation, a process frequently linked to face-to-face communication, emerges in a setting where social development is hindered. Furthermore, the face-to-face group’s outcomes were used as a reference point to evaluate and compare the results of the experimental group. Comparing relationship development face-to-face as opposed to texting is important because in an online situation, nonverbal cues are difficult to detect, leading to a misinterpretation of others’ values and opinions (Echterhoff et al., 2009). The dependent variable was shared reality formation in adolescents, which was influenced by the communication method. The dependent variable was measured utilizing the various data collected in the experimental process and the survey results.

Method

A combination of qualitative and quantitative data was utilized to successfully comprehend the impact of texting in adolescence on shared reality formation. Triangulating the data and interpreting both qualitative and quantitative data added to the credibility of the research. Recognizing participant bias that may influence observations and interpretations was crucial since qualitative data, such as responses to survey questions, lack the numerical ability to draw conclusions. As a result, quantitative data was also taken into account in the analysis process, which provided a concrete numerical value that could be compiled and analyzed to find the statistical significance of the relationship between texting and shared reality formation in adolescence. Current studies analyzing shared reality formation typically consist of meta-analyses or experimental designs with quantitative data. However, my research contributes to the body of knowledge by examining qualitative data and how different communication methods influence how effectively we can understand one another’s perspectives and establish commonalities about the world.

Subjects of Study

Adolescence is a crucial period in a person’s life for social development because it enables young people to develop a stronger aptitude for interpersonal relationships, which equips them to take on more challenging social tasks (Choudhury et al., 2006). As a result, the study consists of 14 subjects who are adolescents, a group of people between the ages of 10 and 19. Because people are aware of when others share their thoughts at this stage of life, the creation of a shared reality is essential because it will affect how people perceive one another in social circumstances. Six of the participants were randomly assigned to the control group, and the other eight were assigned to the control group. Because previous studies had focused primarily on face-to-face communication, I needed to increase the number of participants in the control group in order to specifically study the impact of texting on the formation of shared reality. Due to the requirement that participants physically meet up at the experiment location, which was in the Katy area, and the convenience of most people being close to the experimental location, volunteers were gathered from the Texas city of Katy.

Procedure

Before the experiment, participants completed a preliminary survey describing their perspective on the topic of discussion. Afterwards, I monitored the in-person groups’ scheduled conversations to observe behavior and the discussions that took place. I took note of the particular phrases that the participants used when speaking with one another and watched for nonverbal indicators that might later be compared with the text messages from the texting group. After the experiment, participants were asked to provide access to the messages, and notes were made about how emotions and conversational styles differed online from behaviors observed face-to-face. To prevent discussions from being influenced, participants were completely unaware that they would be taking the postliminary test throughout the whole experiment. Participants and their parents or guardians signed a written consent form before the experiment was conducted to ensure their data could be included in the research. After the experiment concluded, a debriefing period occurred where participants were informed about the true nature of the experiment. The scores of all participants were restricted, and identifiable features such as gender or race were not shared in the research.

Results

Shared Reality Formation in Face-to-Face Group Results

In the face-to-face group, which consisted of six participants, partners were assigned to each participant, resulting in the development of three groups. In the preliminary short answer questions, participants were asked to include their thoughts on whether live action or animated movies were superior. Afterwards, in the postliminary survey, participants were asked to share what their partner’s opinion was on this subject matter after the conclusion of the discussion. The responses to each of the questions are available in Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 5. For the most part, discussions in the face-to-face group were kept engaged throughout the twenty minutes. There were times where the discussions started to fall flat or individuals seemed to be unsure about how to continue talking about the designated subject matter. Regardless, participants reciprocated the energy that their partner displayed when discussing their opinions on the topic. Shared reality formation can be indicated with the use of words that indicate a commonality being formed between participants. All three groups utilized the word “same” on numerous occasions when conversing with each other. Additionally, participants used the word “yeah” when they agreed with what their partner was saying. For example, as mentioned in Appendix D, Participant 6 in Group 3 responded to a point made by their partner by saying, “Yeah, I agree, live action does have a larger audience.” This specific word choice indicates commonalities between participants as the discussion progressed.

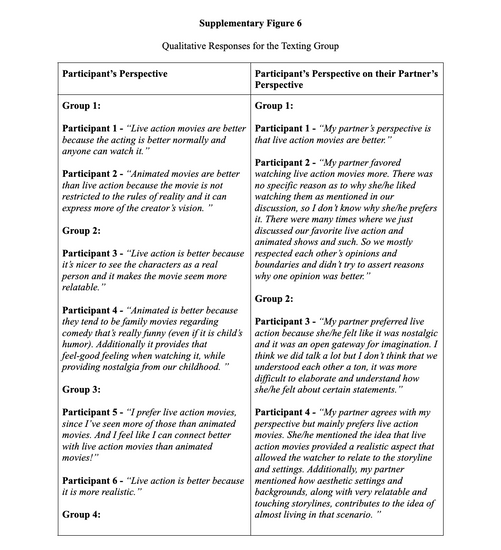

Shared Reality Formation in Texting Group Results

In the texting group, which consisted of eight participants, partners were assigned to each participant, resulting in the development of four groups. In the preliminary short answer questions, participants were asked to include their thoughts on whether live action or animated movies are better. Following the conclusion of the discussion, partners were asked to share their partner’s perspective on this topic in the postliminary survey. Each member of the texting group provided screen recordings of their messages with consent, which made it so that the conversations could be analyzed for patterns. For the texting groups, there was an attempt made by all participants to understand their partner’s perspective, even when it differed from their own. For instance, as shown in Supplementary Figure 6, this can be observed with Group 4 that texted “that’s true I agree there’s more flexibility in animation” and “ohhh yeah i agree.” Texting groups had more discussions compared to the face-to-face group. However, in the texting group, conversations occasionally got off topic. For instance, as presented in Supplementary Figure 6, in Group 3, individuals began talking about YouTube. In the texting group, when individuals felt strongly about a certain subject but were unable to express their feelings through body language, they used all caps and emojis to communicate. This was primarily evident in Group 2’s discussion with the use of the thumbs-up and heart emojis to illustrate agreement.

These conclusions are also supported by the Likert scale statements in which, according to Figure 1, 66.67% of participants in the face-to-face group answered that they either agreed with or were neutral about the statement, “My partner and I had a connection and occasionally finished each other’s sentences.” In contrast, as portrayed by Figure 2, roughly 25% of participants in the texting group indicated they either agreed with the statement or were neutral about it. While the quantitative data was helpful in comparing trends, ultimately the qualitative data was more helpful in drawing conclusions about shared reality formation.

Figure 1: Successful Development of Shared Reality Formation in the Face-to-Face Group

Note. This figure demonstrates the face-to-face participants’ responses to different Likert scale survey questions, organized in a bar graph.

Figure 2: Unsuccessful Development of Shared Reality Formation in the Texting Group

Note. This figure demonstrates the texting participants’ responses to different Likert scale survey questions, organized in a bar graph.

The fact that most groups were able to accurately express their partner’s perspective using language comparable to that used by their partner in the preliminary questionnaire suggests that participants in the face-to-face group felt more secure in their understanding of their partner’s perspective. This can be seen in Group 1, where Participant 1 stated in their preliminary response that they prefer live action movies because “you can understand better” and “it is real.” When asked to describe their partner’s views on this topic, Participant 2 used wording that was similar to Participant 1, stating that Participant 1 preferred live action “because real people act it and it makes him/her understand better.” Shared reality formation allows individuals to feel more confident in their impressions of the world because others share those perceptions. The usage of words such as “same” to denote a shared reality demonstrates that participants clearly felt more confident in their beliefs during the discussion with their partner. Participants also became more at ease as the conversation went on, and as they became more involved in it, they became more eager to talk. In addition, they displayed visible cues such as raised cheeks and maintained eye contact to indicate that they were paying attention to their partner and felt more confident in their responses.

In contrast, participants in the texting group provided longer responses, but the descriptions of their partners’ opinions were inaccurate. This suggests that the texting group’s degree of understanding was diminished because of misunderstandings that made it challenging for them to accurately communicate their partners’ opinions. For instance, as exemplified by Group 2, Participant 4 expressed a preference for animated films because “it provides that feel-good feeling when watching it while providing nostalgia from our childhood.” When asked to explain Participant 4’s viewpoint, however, Partner 3, who preferred live action, responded, “My partner preferred live action because [my partner] felt like it was nostalgic and it was an open gateway for imagination.” Because of misconceptions and a lack of connection in an online environment, shared reality construction is less likely to take place when partners are unable to comprehend one another’s points of view. In the texting group, participants did not share the same beliefs, and an effort was not made to comprehend the perspectives of the others. Because it was difficult to have meaningful conversations via text, even participants who agreed on their preference for live action films over animated films, such as Group 3, struggled to adequately describe their partners’ opinions. The fifth participant, for instance, stated that their partner “had the same opinion as me!” for the “same reasons.” Participant 6 recalled how “when I said I liked live action movies more, she/he [my partner] said me too.” This denotes that participants just recognized that their partners shared their preference for live action and were not completely aware of why they did so. Participants did not exhibit a stronger memory or grasp of their partner’s perspective despite using words including “same” to underline similarities in their ideologies. By labeling the discussions as “one-sided,” Participant 8 raised an intriguing issue, implying that participants had not reached a consensus and were instead merely exchanging their own thoughts back and forth without attempting to comprehend their partners’ perspectives. Participant 3 expressed a similar opinion, saying that although the discussions may have been longer, they were of poor quality because she/he does not “think that we understood each other a ton; it was more difficult to elaborate and understand how she/he [my partner] felt about certain statements.” Participant 2 even admitted honestly that he or she did not “know why [my partner] prefers it [live action].”

Communication through texting can have negative effects on adolescents because, as Gerald Echterhoff and E. Tory Higgins acknowledged, “the absence or privation of social sharing” can have profound influences on an individual’s “feelings of connectedness” (Echterhoff et al., 2018, p. 1). As a result, individuals did not feel the bond that frequently indicates the formation of a shared reality. According to previous research, “vocalizing agreement” can be a technique for creating shared realities in face-to-face interactions (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021, p. 4). Yet, when employed in an online context, individuals will use words such as “same” and even emojis such as the thumbs-up emoji to signify that they agree, even when they do not completely comprehend or entirely agree with the ideas they are mindlessly agreeing to. Emojis employed in texting cannot take the role of hand gestures, body language, and other non-verbal clues that help people grasp one another’s viewpoints and develop shared conceptions of the world, which in turn reinforce their own sense of self. Regardless, by offering a visual depiction of feelings, tone, and context, the use of emojis can aid in bridging the gap between digital communication and face-to-face communication.

However, when participants do not actively try to develop social relationships, it is apparent that the use of specific phrases or symbols does not always signal the emergence of shared realities. Participants in the face-to-face groups were more engaged in the conversations and more certain of their viewpoints as a result of the conversations that validated their beliefs. Participants in the texting group, despite having differing opinions, did not attempt to merge their ideas in a way that would have aligned with their partner. This suggests that there is more of a separation between people when communicating online, and participants were unable to fully understand their partner’s viewpoint, making it difficult to develop inner commonalities about the world.

Conclusion

Based on the research conducted, it is evident that texting has an impact on shared reality formation in adolescents. For instance, due to the lack of interpersonal connection, texting exchanges between teenagers are more likely to result in misinterpretation. Moreover, this research reveals a new understanding that teenagers who frequently text each other tend to prioritize expressing their own opinions rather than building meaningful relationships by actively seeking to understand each other’s viewpoints. Texting also inhibits memory grasp, making individuals less likely to remember conversations that occurred. During the experiment, the face-to-face group had a stronger capacity for conversation engagement, which allowed participants to be more focused on the conversation and confident in their viewpoints. Although the texting group had longer and more frequent discussions, the face-to-face group had more meaningful conversations. This indicates that face-to-face communication motivates individuals to invest more effort in comprehending and modifying ideas to converge with their partner, resulting in greater confidence in shared perspectives. Even though the majority of participants in the texting group initially had different perspectives on the issue—which was unintentional but occurred because the experimental assignment was chosen at random to ensure little bias—the discussion did not even slightly sway their views, which suggests that through texting, participants mindlessly agree to what is said even if their own views significantly diverge from it.

Limitations

The participants’ geographical location in the Katy area posed limitations to the method and data collection process. Because of the experimental method used, participants were required to meet up in person for the experiment, and they all lived in close proximity to one another. In the future, the research would benefit from having participants from a broader geographic area to allow the research to be applied to a broader population and allow conclusions to be drawn that can be applied to the entire age range of adolescents. Additionally, because shared reality development is a subjective process that cannot be quantified in a concrete way, the results were primarily qualitative, and meaning was then derived from the data. As a result, it is possible for some unintended bias to influence the findings. Lastly, shared reality formation is not a process that occurs instantaneously; however, due to time constraints, the data collection could not be expanded over the course of a couple months. Future research on this topic would benefit from prolonging the research to analyze the shift in an individual’s beliefs from the discussions that occur through texting.

Future Directions

Since technology is constantly evolving, there are numerous future directions this research can take. For instance, future research could examine how conversations will probably change as a result of the recent development of AI chat bots, which are frequently used to format emails and get guidance on how to express our emotions and write messages to others, resulting in our ideas being less authentic than they would be in a face-to-face setting. Also, depending on how users interact with AI chat bots, they may be exposed to biased or misleading information about a particular subject, which may have an impact on their own beliefs and how they communicate this knowledge to others. This research can also be applied to analyze how, through social media, individuals can distort their identities due to the diminished influence of social norms. Future research would benefit from extending the time frame of the research to allow for even more accurate results with more concrete evidence to indicate how shared reality formation is impacted by texting. This research can be used to indicate the urgency of recognizing how texting impacts the development of crucial social skills in adolescents and impairs their ability to form relationships in the future. This can impact the ability of adolescents to succeed in interviews or in business meetings in which effective communication and collaboration are key. Furthermore, strong social skills are necessary for networking since they allow a person to start discussions, develop relationships, and create long-lasting connections with people. The study emphasizes how crucial it is to investigate the drawbacks that prolonged texting might have to develop a thorough understanding of the problem. While this study suggests that texting has an effect on how shared realities are formed based on qualitative findings and outward displays of emotion, future research can benefit from examining how texting has long-term impacts on regions of the brain such as the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the anterior cingulate cortex, which are responsible for social decision-making and emotional response.

The duration of the research process has enabled me to develop personally by providing opportunities to learn how to respond more effectively to challenges and setbacks. For example, during the research process, due to time constraints, I had to conduct an experiment in a shorter time span, requiring changes to my initial plan. Yet, through this experience, I gained valuable skills in being adaptable and ensuring that my research was comprehensive by utilizing more effective approaches to address my research topic. Additionally, due to the prolonged and complex nature of the research paper, I also enhanced my ability to plan and organize my thoughts in a more structured and efficient manner.

Overall, this research has major implications for the adolescent age group, in which texting is a prominent method of communication and social development occurs. It is vital to conduct further research as communication not only affects personal relationships but also communication in professional settings. As a result, it is crucial to understand the implications of texting on relationship

Supplementary Figures

References

Brignall, T. W., & Van Valey, T. (2005). The impact of internet communications on social interaction. Sociological Spectrum, 25(3), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170590925882

Choudhury, S., Blakemore, S. J., & Charman, T. (2006). Social cognitive development during adolescence. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 1(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl024

Echterhoff, G. (2013). How communication on the internet affects memory and shared reality: Talking heads online. Psychological Inquiry, 24(4), 297–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43865653

Echterhoff, G., & Higgins, E. T. (2018). Shared reality: Construct and mechanisms. Current Opinion in Psychology, 23, iv–vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.09.003

Echterhoff, G., Higgins, E. T., & Levine, J. M. (2009). Shared reality: Experiencing commonality with others’ inner states about the world. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(5), 496–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01161.x

Graham, J. B. (2013). Impacts of text messaging on adolescents’ communication skills: School social workers’ perceptions. SOPHIA. https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/184/

Heiphetz, L. (2018). The development and importance of shared reality in the domains of opinion, morality, and religion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 23, 1–5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.11.002

Lieberman, A., & Schroeder, J. (2020). Two social lives: How differences between online and offline interaction influence social outcomes. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.022

Novak, M. C. (2019). A brief history of communication and innovations that changed the game. G2. https://www.g2.com/articles/history-of-communication

Rossignac-Milon, M., Bolger, N., Zee, K. S., Boothby, E. J., & Higgins, E. T. (2021). Merged minds: Generalized shared reality in dyadic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 882–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000266

Schmalbach, B., Hennemuth, L., & Echterhoff, G. (2019). A tool for assessing the experience of shared reality: Validation of the German SR-T. Frontiers in Psychology, 10:832. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00832